Of course it is Elizabeth Bishop’s phrase, from “Crusoe in England,” though I would have first read it in Christine Schutt’s A Day, A Night, Another Day, Summer, where she borrows it for the title of a beautiful, inscrutable, foul story that, happily, you can read right here. (She gives us our dek.) Actually I wouldn’t have read the Schutt first; my Complete Elizabeth Bishop is from a 101 poetry workshop in what must have been 2001. It was many years and states later that I fell in love with Schutt’s work (sorry, MP). At a certain point it occurred to me to source the title of this story, which I’d figured would be Emily Dickinson because she’s a big one for Schutt, but instead it led me back to this Bishop book I’ve owned since I was 19.

Amanda and I spent a week in New York City. It was wonderful as always: noisy, hectic, dysfunctional, a fortune. Almost everyone was in a great mood even as they made their lives sound miserable. Rent up, subway sucks, jobs scarce, pay bad, childcare hell, indicted mayor, lantern flies. Everyone wants to get out and can’t or wants to stay and can’t. I am very very glad that these are not my problems. And still I miss it.

I was on a panel at the Brooklyn Book Festival; I got to see my friends Anika Jade and Madeline Cash read at a weird loft for a magazine that maybe doesn’t exist or else exists as the reading (unclear, didn’t ask); I ducked into the Drawing Center to get out of the rain and wound up staying for an hour; I hung out with my friend Lisa’s cats (also with Lisa); I walked Prospect Park from top to bottom and met up at the Picnic House with some colleagues and students from the low-res MFA; I had coffee with Sofia Wolfson, whose album Imposing on a Hometown I’ve mentioned several times before—it’s one of my favorites of the year; I got invited to a luncheon celebrating Czech literature at the Bohemian National Hall, where I had nothing to contribute but my presence and they fed us goulash and schnitzel and I met the future of Czech literature and ran into some people I hadn’t seen in years. I saw a white ladder all covered with water, etc.

I had dinner with my friend Adam and his family south of Windsor Terrace near where they live now and because the kids are little we met at 530. After we ate I walked them back to their building and then it was maybe 730 and I was on my own again. I caught a Q train heading not exactly toward Williamsburg where I was staying, but toward a towardness I wasn’t exactly rushing toward. I’d been trying for several days to pick up the new Tony Tulathimutte but three bookstores hadn’t had it. I wondered if Unnameable Books might. I always try to get there at least once when I’m in town, so I hopped off the Q at 7th Ave and it was, I don’t know, a ten minute walk to the store. Well after 8 by this point but Unnameable is open till 11. There was a reading happening in the back garden. Someone was explaining how we have to resist surveillance—not just the devices and the networks, but the way in which the knowledge of their presence deforms our relation to ourselves. She was right and I listened for a while. Unnameable didn’t have Tony’s book either but they did have the newish Verso edition of Adorno’s Minima Moralia. I’ve read most of this book in bits and pieces over the years but hadn’t owned my own copy or read it front to back before, which is what I’m doing now. New York!

The next day I drove up to Vassar with my friend Tracy O’Neill to visit her class, which had read Reboot, and my friend Ryan Chapman’s class, which had read the title story from Flings. I’d never been there before. Unsurprisingly, a beautiful campus. (Elizabeth Bishop is an alum; this might have been what got me thinking about her.) Their art museum has a Rothko, a Pollock, an eerie and gorgeous Alice Neel, ample requisite Hudson River School.

It is always a privilege to meet with groups of students who have read my work and are excited to talk about it. It is an honor—and humbling—to be read and read well. And to think that something of mine might be some small part of a young writer’s developing sense of what’s possible—what’s worthwhile—in the discipline. That they might some day have cause to write a line about Reboot like mine above re Bishop: I first read it in a workshop in what must have been 2024, and the guy who wrote it actually came to class, I think my prof knew him somehow; weird to think now that I’ve owned this book since I was 19.

Not to put myself in the same tier as Elizabeth B., only to say that a lot of what turns out to be foundational to any writer’s or reader’s life is out of their control. It’s what is assigned to you by the teachers you happen to have wherever you happen to have gone to school, a choice that was like as not partially or entirely out of your hands as well. You go where you can afford to go, where you can get in; you go somewhere because you want to be near your family—or because you don’t. When you get there you sign up for a class based on a course number, or the time of day it meets, or a three-line description in a catalog. You can’t expect that the novelist Ryan Chapman is going to bring in Justin Taylor to talk about a short story of his from ten years ago and that, even though it’s an obviously auto-fictionish story about Portland hipsters in the mid-aughts, Justin will spend a considerable amount of time claiming it’s actually a stealth homage to Virginia Woolf’s The Waves which he was assigned in a Modernist literature class when he was your age, seasoned with a bit of Mary Gaitskill’s “Heaven”, which he has long suspected is a stealth homage to To the Lighthouse, but that he wrote it in the formal style of one of those late Barry Hannah stories (lot of momentum, no section breaks) as a response to his own first book (which you have not read) because that one was riven with Lishy white-space and he wanted to see if he could do it a different way.

Maybe you don’t get anything out of such a talk other than a list of names, or the revelation that you don’t need to run from your influences: you can run through them instead. You can cross-breed them like plants or pit them against each other like scorpions in a jar. Maybe what you get is a powerful negative example: middle-aged white guy blathering for 45 minutes about self-indulgent bullshit. You vow to never, ever become such a person. These are all plausible, worthwhile outcomes. My point is that the outcome isn’t up to me, isn’t knowable to me, anymore than the teacher to whom Reboot is dedicated could have known (or I could have known) that the semester I spent in his lit seminar would become one of the most important intellectual and aesthetic experiences of my life and 20 years later I’d more or less scaffold a novel with his syllabus. I was just a guy trying to take a cool-sounding class and he was just a guy trying to teach one. Which is what I am now, what my friends are. One can’t and shouldn’t focus too much on this idea of future-retrospective value, because it’s totally pointless and more than a little bit vain. But it would be dishonest, and I think a mistake, to neglect or disavow it entirely. We’re creative writing teachers, not doctors: this isn’t life or death shit. But the people we’re working with are people who mostly want to be writers, not doctors, so for them it actually kind of is.

What I’m trying to say is that I hope I gave the Vassar students something useful because what they gave me was an incredible gift. Two gifts, in fact, in one day—dayenu.

After the class visits we had dinner with Amitava Kumar, whose novel My Beloved Life I recently read and greatly enjoyed. And more than enjoyed, admired—for its quiet poise and lucidity, for how it is packed with detail yet uncluttered (“And what noticing!” as James Wood rightly had it), for its surehanded modulation of narrative time and scope: holding in the same hands a man’s life and the sweep of a country’s century, the reverberations of that life and century in the life of that man’s daughter. If someone asks me for a Best of ‘24 list, this will be on it.

Another thing I did while I was in New York was meet up with two editors for whom I write book reviews. One I’d never met in person before and the other I’ve been working with for many years. It got me thinking about my parallel career as a book critic. Parallel, that is, to both my teaching and my fiction-writing, with the relationship to the former rather less fraught than to the latter. I mentioned this in passing in the “Standing In the Doorway…” essay I published here last month. It also came up on the Brooklyn Book Festival panel. I forget the question that provoked it, but I said that the reason I write book reviews and literary criticism (themselves separate though related practices; set that aside for now) is because I find it creatively rewarding in itself. I love the way it invites me to attend to a given work, engage it on its terms and tease out my own reactions thereto, then re-convert that refractive inwardness into something shareable, public. (I may not have said all of this on stage at the panel.)

I think there is unique literary-cultural value in fiction writers writing about each other’s work. This value is separate from the value of criticism produced by self-identified professional critics. I don’t expect, or even hope, to match or best the best we have—Becca Rothfeld, Christian Lorentzen, and Parul Sehgal, for a start—because my referential frameworks, my motivations for writing, and my method of approach are all different from theirs in a way that theirs—however distinct in style and prerogative—are fundamentally aligned with each other’s. What I mean is that the novelist-critic’s calls are always coming from inside the house.

My own critical practice is modeled (however aspirationally) on that of other novelists: my teacher David Gates, who btw loved Rothfeld’s book which along with Kumar’s is one of the best books published in ‘24; Lorrie Moore, whose See What Can Be Done I cannot recommend highly enough; Joy Williams’ rare bracing interventions and encomia; ditto Mary Gaitskill’s and Zadie Smith’s. Or books like Martin Amis’s Moronic Inferno. I get why some writers mostly avoid writing criticism or foreswear it entirely. They feel it’s compromising in some way, ethically or artistically, or they simply don’t want to be responsible for another writer’s failure or success. All fair enough. But I wish more would take the risk. We all write to be read, and reviews and criticism are some of the most substantial proof we ever get that someone is actually reading us. I cherish the smartest and/or most surprising reviews my books have gotten. These are not necessarily the most positive reviews, they’re the ones that told me something about my own work that I didn’t already know. I want to do that for other writers as best I can.

This is what a book of my collected criticism would look like if it were bought today. It’s not exhaustive, but it’s everything I’d want to see gathered and preserved. With a few notable exceptions, the longer pieces (2500+ words) are career retrospectives on major living/recently deceased American writers. The shorter pieces mostly focus on debuts. I’m not presuming that the fossil record of Justin Taylor’s critical attention has any specific value, now or in the eventual historical sense. But I am suggesting that it could, as a catalog of my reverence or dissent for—or, more accurately, my agon with—the writers in the generations before mine, those who came up alongside me, and lately some of those in the generation below.

This screenshot is a user profile. It’s a ghost map and a rap sheet. It’s a shadow history of my first five books, recording not only the evolution of my aesthetic interests and thinking about literature (including limitations, biases, and lacunae) but my actual working life. Who let me write for them and how often and about what and at what length. Total critical output year on year. As you might imagine, that measure is inversely correlated to the one in the screenshot of my uncollected short fiction that I am not showing you. When that wasn’t working, I did this. When I couldn’t sell or finish a book, when I couldn’t find an adjunct class but still needed dental work, I did this. (If I really wanted to press this point I’d have put the word rates next to the word counts.)

This list also offers a glimpse of what a small group of preeminent publications thought was important during the 2010s and 2020s. Some of you know the biz well enough to read the names of specific editors behind the names of the magazines: who was working where when, who likes me and who thinks I’m full of shit. NYTBR has always been pretty good to me; Bookforum has been my most consistent and generous home. WaPo work started about a year ago and is going great. Harper’s every now and then: I can’t always capture their interest but when I do they give me the space I need. I’m hoping to write for The Point again soon: the Portis piece I did for them was a blast to work on and it got a huge reaction when it came out. Note too the publications that do not appear here. Some I’ve never pitched, some have never acknowledged the pitches I’ve sent. A few have asked me for stuff when I haven’t had anything to say and/or the time to say it. So it goes.

Whatever else it is or isn’t, this list catalogs for posterity’s judgment what books were deemed worthy of coverage, and of what kind and by whom, when they were new. If we assume a future where that might matter to someone, whether a young novelist or a historian of 21st century American fiction, this is my contribution (so far) to their work. The actual content of the reviews, i.e. the artistic/intellectual value of said contribution, will be judged by posterity as well, but separately, and I say that with full understanding that consignment to oblivion is as legitimate a judgment as any other.

Let’s close this out on a lighter note with some music stuff (sorry, Charley). Allegra Krieger made a playlist from material in the Smithsonian Folkways Archives as part of their People’s Picks series. It’s wild. Also wild is “Cardinals at the Window,” a 136-song benefit comp for flood relief in Western North Carolina. Ten bucks (or donate more) with 100% of proceeds split evenly between Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Rural Organizing and Resilience (ROAR), and BeLoved Asheville.

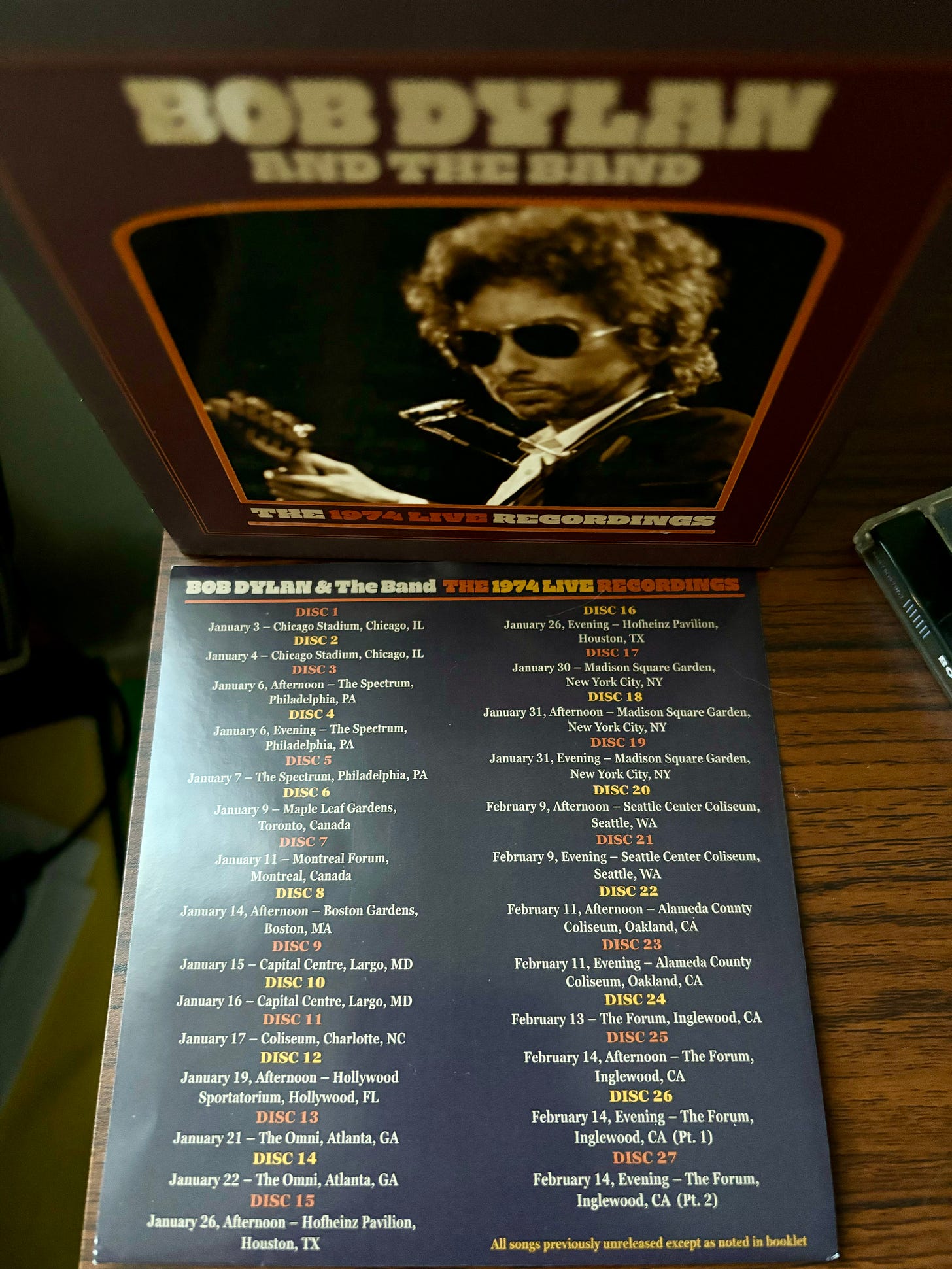

And here’s one of mine. I was digging around in Joni Mitchell’s Archive releases and noticed that early on she covered some of the same folk songs Dylan did. (No surprise there, everybody covered them.) So I paired up their versions of what I could find: “House of the Rising Sun”, “Tell Old Bill”, “Copper Kettle”, “Dink’s Song.” Then I remembered that bizarre Dylan cover of “Big Yellow Taxi” so I threw his and hers on as well. Then I got a little loose: two Guthrie covers but not of the same song, her “Pastures of Plenty” vs. his “I Ain’t Got No Home”; ditto Cash, with her “Me and My Uncle” (!!!) to his “Ring of Fire.” Then her original song, “Coyote”, which she wrote while on tour with Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue. In the intro to this live version she talks about having finished writing it the night before. Paired that with his “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You” from the same tour.

Thanks as always for reading.

Lantern flies! Weird lofts! Burrata! Alice Neel IS eerie, her work creeps me out and that is also maybe part of its appeal? How cool to accomplish both in a work. Guess I’ll just have to add Ratner’s Star to my TBR and aspire to be the fourth. ⭐️