Report cards

I reviewed Megan Nolan’s Ordinary Human Failings for the Washington Post, part of my ongoing gig as a contributing writer to their books page. Since WaPo’s paywall is basically unscalable, I’m screencapping my favorite paragraph from the review (from my Word doc, not the published version, I can’t scale it either ):

(A bit more of me on Trevor here.)

There was a second piece I thought I’d be linking to this month but it’s still impending so, you know, thoughts and prayers.

In the meantime, Reboot has been getting some generous notices, most recently this profile in Publishers Weekly, and a tour is shaping up: L.A. the weekend of 4/20; Portland on 4/23 in conversation with Jon Raymond at Powell’s downtown; 4/24 at Third Place Books (Ravenna) in Seattle; 4/29 in Vancouver WA at Clark College in conversation with Andrew Leland about his book In the Country of the Blind; McNally Jackson (Seaport’s version) on May 1; and back in Portland on May 10 (→Powell’s reprise) in conversation with Julia Hannafin about their amazing debut novel, Cascade, which I had the privilege of reading early and blurbing.

You’re thinking to yourself that I have failed to provide key details like precise locations and times—and why not just slap it all together in a convenient JPEG that can be shared on social media? Save that sort of sanity and competence for the March issue. Hopefully by then there will be a couple more dates on the schedule. And not to put too fine a point on it, but if you’re a person who books writers for stuff, I’d be just chuffed if you’d consider me for a talk/reading/class visit/&c.

Oh and I joined Instagram. Less chat, more cat.

Here’s what I said about Julia’s novel:

Another debut novel, out the same day as Cascade (April 16), is Norma by Sarah Mintz, from the Canadian indie press Invisible Publishing. I had never heard of this press or this author, the book just showed up at my house, like so many (too many) books do. I gave it what was meant to be a cursory peek before consigning it to the purgatory of the ARC pile. Instead, this happened:

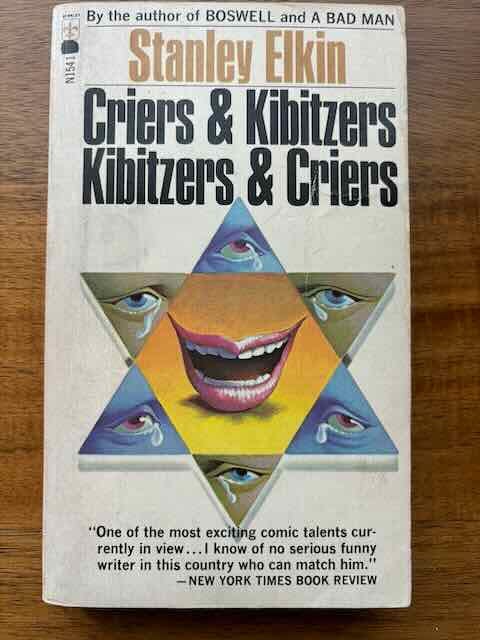

Mintz published a short essay about the writing of Norma, its (and her) relationship to Jewishness and postmodernism, with particular attention to Stanley Elkin’s novella The Bailbondsman, which I’d never read before but picked up on account of Mintz’s interest. (Caveat emptor: racism, some of it the subject of Elkin’s satire and some of it alas seemingly Elkin’s own.) Elkin, one of the funniest writers of the 20th century and a true genius at the level of the line—think Amis, Hannah, Faulkner, Woolf—is at this point so marginal a figure that part of the pleasure of reading him is feeling like you’ve got him all to yourself. I suggest starting with either The Living End, The Franchiser, or his only story collection, the impeccably titled Cries & Kibitzers, Kibitzers & Criers (1965), which I own in an edition with a cover so insane that I’m going to stop writing this and go get it so I can show you:

Gone are the days, boy. There’s a later edition of this book (Dalkey Archive reissue?) with a preface in which Elkin claims to have invented the Polish joke. Just in case there’s any residual confusion about what we’re dealing with here.

About that vault (disambiguation)

I’ve got twenty (20) short stories sitting on my hard drive, all but three of them published since Flings came out in 2014. The urge to write stories comes to me far less often than it used to but the stories tend to come faster when they come at all. That’s a mixed blessing: they have an organic velocity and internal coherence that I prize highly (and used to have to work had to achieve) but they’re tougher to revise because they already know what they want to be when they get here. And they do still need revising, if only to become better versions of themselves.

The short story is still my favorite form, but sometimes it occurs to me that between my two extant collections and the 20 on my hard drive (setting aside juvenilia and misfires) I’ve produced just shy of 50 stories over the course of my career. I look at that number and am proud of it, but I also sometimes think, How many more of these fucking things am I supposed to write? At this point, one or two a year feels like plenty.

That said, I’d really like to publish a third collection, and there are reasons to think that I may get the chance to do so, but who knows when, or what portion of the aforementioned 20 stories will be included. (I’d guess between half and a third.) In the meantime, some of these stories are available online in the archives of the journals/magazines/websites that published them. Others aren’t.

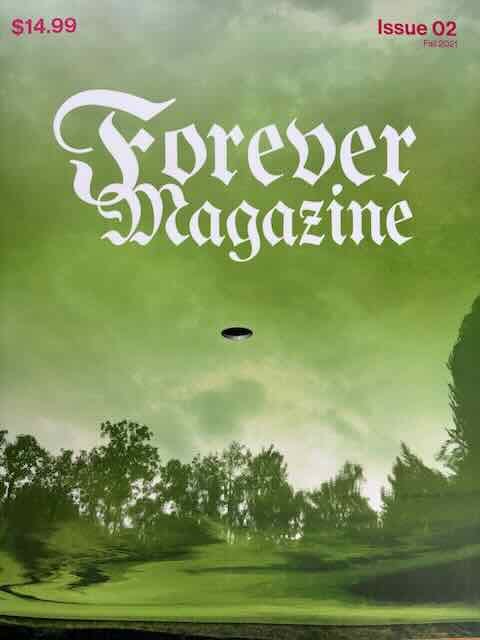

One that isn’t is called “Medical Lake”, a jumped-up flash fiction (~1200 words) that I gave to my friends Anika Jade Levy and Madeline Cash for the second issue of their magazine, Forever. At the time (deep pandemic) I was going a little out of my mind (not special) and feeling extreme antipathy toward social media and the internet in general. I liked that Forever was small circulation, very under the radar. #1 was a staple-bound zine that Madeline mailed to me. Then #2 came out, with my story in it, perfect-bound with a cover by Ryan Trecartin, which should have been a clue as to where things were heading. That’s not a dig.

You may not need me to tell you that Forever is on the radar now. I mentioned Madeline’s collection Earth Angel in my 2023 recap; she has a story in the new issue of the Sewanee Review. Anika sold her novel, which will be out next year from Catapult. Forever is about to publish issue #6. They’ve got a lot to be proud of. They’ve grown the zine into a full-color glossy, kind of a zoomer Parkett on good acid and bad speed (also not a dig; art direction by Nat Ruiz) full of writing that resonates with what you used to find in the New York Tyrant and can still find in NOON or X-RAY LIT, but it doesn’t feel beholden to any of those things. I’m somewhere on the edge of that Venn diagram, insofar as I was in the Tyrant twice, NOON never (not for lack of trying), and I assume the kids at X-RAY have no idea who I am. It meant a lot to me that they published this story.

Anyway, back to issue #2: because I was being insane about the internet, I told them not to post my story to their website. I was emphatic that it be in print only; it felt imperative to only be read by people with the wherewithal to get their hands on a physical copy of the magazine. These days I feel more ambivalent than antipathetic re internet stuff (see above re Instagram), Forever #2 is totally sold out so you can’t get one, and it has lately occurred to me that one function of this newsletter could be to give new life to old writing during its who-knows-how-long (perhaps forever) limbo between magazine and book. So we’re gonna try it.

Here is my story “Medical Lake” from Forever #2. For the foreseeable future, this is the only place you’ll find it. It’s one of those ones like I was talking about earlier: velocity and coherence. I’m not saying it’s genius, but it moves. And is about movement, whatever else it’s about. I hope you like it. As a reminder (hi, Mom) you have been reading nonfiction up to this point and what follows is fiction, so please metabolize the narrative “I” accordingly. “Medical Lake” is from a series of shortish place-based stories written loosely in the spirit of the Texas/Florida/South Carolina sequence in Padgett Powell’s collection Typical (1991). The other places treated in said series are Indianapolis, Missoula, and the Florida Panhandle: all places where I’ve spent enough time to feel like more than a tourist but still far from a local. I tried to do Iceland too but it wound up 7000 words long and kind of about Florida anyway and nobody will publish it. Maybe someday it’ll find its forever home. Or maybe I’ll just post it here.

MEDICAL LAKE

I asked for spinach instead of lettuce, for a wheat wrap instead of a footlong, lite mayo but you know what make it double roast beef because there is such a thing as limits. I was trying to be better but a man has limits as to what he can self-inflict. I hadn’t expected to reach mine here, at this rest stop by Medical Lake, Washington, but I was hungry and less than halfway to Bozeman, Montana, where certain humiliations awaited. I’m loath to discuss those. “Maybe good,” I told the sandwich maven, “if you add some bacon, too.”

“This one fat wrap,” she said, perhaps admiringly, grudging the tortilla through its final fold and tuck.

“I’m eating half for dinner,” I lied. I was going to eat the whole thing in my parked car immediately subsequent to this transaction. I paid up and set out for the lot.

Across from the rest stop was the fulfillment center, blue smile swooping along its highway side. It was a huge and hulking thing that appeared diminutive and forlorn against the gray flat West, with nothing for miles in any direction save this rest stop and, I assumed, the town of Medical Lake and the lake that it was named for, though neither town nor lake were visible from where I stood. The fulfillment center looked like a prison and even had a prison’s narrow winding approach road down which, I now saw, a small figure walking against traffic. Not that there was traffic.

I chewed and watched the road, savoring the squish of lite mayo between my teeth, struggling to swallow the golf ball of beef mash in my mouth. I pictured its pinkness against the pink of my esophagus—lightless gully of my gullet, acid aquifer of my gut—doing like it says in The Secret until I successfully sucked it down.

I went back into the rest stop to hit the Starbucks, my balled-up wrap wrapper in-hand, bound for their waste basket instead of my backseat; I was glad.

I had got my latte and was walking back to my car when I saw that the figure from the fulfillment center had made it to the edge of the rest stop parking lot. She wore Doc Martens, black jeans and turtleneck, pink hair peeking from beneath a black watch cap pulled tight over her ears. Breath puffing in the cold as she walked, though some of that was the vape pen she puffed on, its red eye in bruised contrast to her wardrobe and the leaden sky.

I sipped my latte, leaned on my car—a kelly green Camry—and played cool.

She had been living in Medical Lake, she told me, and working at the fulfillment center, though she’d just now quit. “Unfulfilling,” she quipped through a vape cloud. She was looking to get to Billings and I told her I was good for most of that way.

I admit I was already starting to get ideas: loud music and someone to talk to, pushing 90 on I-90 in high camaraderie, verge of cahoots. After that who knew. Maybe she had pierced nipples and four hundred dollars rolled up in her sock. Maybe Bozeman and Billings both could be avoided. I mean I didn’t know what she was headed for but I figured one thing we had in common was that neither of us was eager to meet our fates. Maybe, I thought, we’ll turn north and disappear right up the Idaho stovepipe, blasting Robert Earl Keen as we cruise past Sandpoint and Bonners Ferry, gone like smoke, blown away toward some new life beyond the Canada line.

Is there even a crossing up there? I had never been and not to spoil my story but I still have not.

Because it might have been the latte in combination with the double roast beef or it might have been that the lite mayo had sat out on the counter for some hours, but my stomach was doing elevator drops by the time we hit Idaho and the last thing I wanted was to shit myself at the top of Fourth of July Pass, so we stopped at another rest stop, another Starbucks, this one in Coeur d’Alene, and I bought Sheena—which was her name; mine’s Howie—a can of cold brew, stuck two bucks in the tip jar and begged the barista for the bathroom code.

The barista gave me a look like she didn’t like my face—and sure, I was sweating, likely a bit peaked—but she yielded up the blessed numbers and soon I was sighing as I sagged onto the cold white throne to inaugurate an evacuation so vast it left me breathless, sort of windswept, clenched and rubbery, a steely flaccidness disrupted by seizures of dispatch that came on like orgasms and crashed like trucks.

I found out later that I popped a blood vessel in my left eye, and I guess I must have been moaning, because all of a sudden I heard the electronic door lock beep, its innards in motion. I swept my hands across my junk but made no move to stand.

The barista stood in the doorway with a Naloxone syringe unsheathed and gleaming in her food-grade-gloved hand.

“Hoo oh,” she said. “Sorry but it was fifteen minutes so I figured.” She backed out, fist over her face to spare me her giggles and herself the smell. The door closed, the lock grumbled, I was safe again.

When we got back on the road, Sheena drove while I nursed a raspberry SmartWater. There was snow in the pass but not much. We had something but it wasn’t camaraderie; cahoots were out of the question; they were as far from us as that Canada line.

I allowed myself to drift toward a weak recuperative sleep and as I drifted my thoughts were not of Sheena nor of Lookout Pass, the next one, which was coming up fast, nor yet of the humiliations I had suffered this day nor those that awaited me in Bozeman. Neither did I think of my burning nethers and wretched guts.

What I thought of was the time in fourth grade when I won the class poetry bowl by writing that the sky was like a Goodwill blanket the size of forever, tucking us in to the great big bed of the world.

I remembered the ten dollar bill I was awarded for my winning poem and how proud I was handing it to my mother so she could see it for herself because she was, she said, so proud, and just had to see it, had to hold it for a minute, and how I did not allow myself to know in my mind what I already knew in my hammering heart.

I had never won anything before I won the poetry bowl and I have never won anything since.

I don’t know what Mom spent my money on but I can guess, like I can guess that Sheena’s got stories like mine and worse, but there was one thing I did wonder about and could not half hazard a guess at, I mean it was my real last thought, not what I said earlier about my poem, though that was close.

My thought was, What makes a lake medical?

I would still like to know.